Submission Details

In this exercise, you’ll practice writing recursions on trees. In part I, you’ll be working with ancestry trees. In part II, you’ll be working with binary search trees (a specific kind of tree) (note: we won’t talk about BSTs until Friday in-class but you should be able to complete everything except list-all-ssns and lookup with just the stuff in the pre-recorded lecture + Monday).

Part 1. Ancestry Trees

Everybody has exactly two biological parents. They, in turn, each have two biological parents, each of whom have two biological parents, etc., going back more generations than we care to keep track of. We can diagram this genealogical idea as a tree structure made up of roots and leaves. If you look at a tree drawn in what’s called root at the bottom format, the root is all the way at the bottom of the diagram and the leaves are above it, connected by arrows. This will probably look most familiar to you in terms of a “ancestry tree.” If you’ve taken a math class that deals with trees, you’ll also probably see this as a familiar format. However, in computer science, we often use a different format: root at the top. Check out the difference below:

Root at the Bottom

Root at the Top

Note

Of course, this is an over-simplification of what a true genealogy looks like. For now, we're going to abstract away other elements of these tree structures like step-parents, adoption, etc., to limit the scope of the assignment. If by the time you're finished, you're still enjoying working with these structures, try adding these elements to your functions (but make sure that your submitted assignment matches the requirements described below).

There is really no difference in the data these trees represent. It’s literally just a difference in appearance. I often find it easier to think of these things in terms of your own lived-experiences, so here’s the same exact structure, just with my family’s chosen names inserted into each node.

Root at the Bottom

Root at the Top

While this is a great graphical representation of a tree, how do we encode this information in 1. a way Racket can understand and 2. a format on which we can compute? We can start by introducing a new struct called human.

(define-struct human (name parentA parentB))

Note: We’re calling it

humanrather thanpersonbecause we’re making a differentstructcalledpersonfor Part 2.

A human object represents a person and specifies their name (a string) and their parents (more humans; parentA and parentB). But if their parents are also human objects, then they have parents, who are also humans, and so on. Eventually, we’re going to get tired of listing off one’s 8th generation ancestors and just leave the parents blank. The way we’ll specify that a parent is left blank is by using the value empty, which is just another name for the empty list '().

So here’s the code for making, for instance, my ancestry tree:

Show Code Example

(make-human "me"

; your parentA

(make-human "mom"

; mom’s parentA

(make-human "nana"

; papa's parentA

empty

; papa's parentB

empty)

; mom’s parentB

(make-human "papa"

;; papa's parentA

empty

;; papa's parentB

empty))

; your parentB

(make-human "dad"

; dad’s parentA

(make-human "grandma"

empty

empty)

; dad’s parentB

(make-human "grandpa"

empty

empty)))

Notice that the parentA and parentB fields for the second set of grandparents are just set to empty to avoid having to keep typing forever. Again, that’s just our way of saying “we’re not recording further information here.” Once again, this gives us a way of inductively defining what an ancestry tree is. It’s either empty, or a human, with two more ancestry trees for parents (either or both of which might just be empty):

; An ancestry-tree is either

; - empty

; - (make-human string ancestry-tree ancestry-tree)

Why does this matter?

This means we have a perfect starting point for writing recursive functions that process ancestry trees. If an ancestry tree is either `empty` or a `human` with two more ancestry trees, then our basic skeleton for writing some recursive function is going to be something like this:(define (func tree)

(if (empty? tree)

; Base case: the empty tree

write-what-you-output-for-the-empty-tree-here

; Recursive case: it’s a human

(combine-answers-somehow (human-name tree)

(func (human-parentA tree)) ; left branch recursive step

(func (human-parentB tree))))) ; right branch recursive step

Processing Ancestry Trees

In the starter file, exercise_5.rkt you’ll find another example tree (the…somewhat strange family tree of some characters from Game of Thrones). Your job will be to write a series of functions to process not just that example, but also any possible ancestry tree. For clarity, we’ve provided signatures, purpose statements, and tests (though these aren’t exhaustive). For the tests in Activities 1 and 2, it is okay if your functions produce a list where the names appear in a different order from the given examples. That’s OK as long as the list contains the same elements.

Visualizing an ancestry-tree

To help you visualize ancestry trees, we have provided the function

Activity 1. ancestors-names

Write a function that, given an ancestry tree, outputs a list of all names in the family, including the person’s own name.

; ancestors-names : ancestry-tree -> (listof string)

; returns a list of all of the names of one's ancestors including

; one's own name

(define (ancestors-names pers) ...)

So if called with, for example, my ancestry tree from the beginning as an argument, it should return all the names including “me”:

'("me" "mom" "nana" "papa"

"dad" "grandma" "grandpa")

Don’t worry about duplicate names in the list. If there are two ancestors with the same name, just return them twice.

Activity 2. my-ancestors-names

Given an ancestry tree, give a list of all names in the ancestry, except the person’s own name. So if called on my example tree, it should return all the names except “me”.

; my-ancestors-names : ancestry-tree -> (listof string)

; returns a list of the names of one's ancestors excluding one's own name

(define (my-ancestors-names pers) ...)

Activity 3. are-they-related?

Now write a function that can determine if two trees have a common ancestor, in other words, if any of the names appearing in one tree also appear in the other tree.

; are-they-related? : ancestry-tree ancestry-tree -> boolean

; returns true if the ancestry trees have a common ancestor

(define (are-they-related? f1 f2)

...)

Reminder!

You can run these function calls in the Interactions Window to visualize the trees in the last

(draw-ancestry-tree tytos) ;; example 1

(draw-ancestry-tree tommen) ;; example 2

Hint!

Remember you just built functions capable of generating a list of a person's ancestors. Now you need a helper function that takes in a name and a list and checks to see if that name is in the list. You can build your own using recursion or check to see if there's a built-in one on our Quiz glossary. Finally, you'll need to use one of our iterators or build your own to see if any of the elements of one list return true using the function you made (or found).

Part 2. Binary Search Trees

Searching a collection of items is a common task. For example, you might be running a company with a ton of employees, each of which is a person, stored on a computer. Each person has a name and a social security number (SSN) (a unique numerical identifier of the form XXX-XX-XXXX, assigned to U.S. citizens and other residents; in our exercise, they’re just regular numbers).

; a person is

; (make-person number string)

(define-struct person (ssn name))

Visualizing person objects

We have provided a function

Ideally, you’d be able to quickly ask questions like “is there a person with the SSN 111-22-3333?” so that you could, for instance, quickly find their details in your Human Resources database.

If you put all your person objects in a list, then there really isn’t any better way of answering this query other than starting at the beginning of the list and looking at every item in the list until you either find what you’re looking for or you reach the end of the list. In the best case, the person is right at the beginning of list. In the worst case, you have to look at every item in the list.

A binary search tree (BST) is a popular way of organizing data to make it faster to search. The basic idea is that whereas a list just has one “link” to the next item in the list (the rest link), a binary search tree will have two links: one to all the persons with a smaller SSN than the current person (in the data attribute), and one to all the persons with larger SSN.

; A binary-search-tree is either

; - false

; - (make-node person binary-search-tree binary-search-tree)

(define-struct node (data smaller larger))

; INVARIANT (a quality that holds true for all objects of this type):

; every person in “smaller” binary-search-tree has a smaller SSN than data, and

; every person in “larger” tree has a larger SSN than data

Remember that SSNs are unique so you don’t need to account for duplicate SSNs. The invariant on binary search trees is useful when searching for or ordering people. For example, if the SSN we are looking for is less than the SSN in the current node we don’t have to look in the right portion of the tree at all! This makes this method of storing data, potentially, much faster than the version that uses lists.

Visualizing a BST

We have provided a functionIn the starter code, zhang-node is the largest binary search tree we’ve provided. You can similarly use (draw-bst zhang-node) to see what it looks like when using it to test your code.

Activity 4. Organizing data into binary search trees

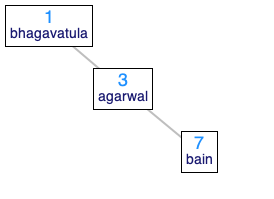

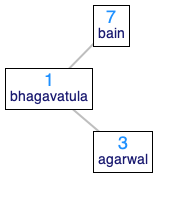

Just because BSTs have an invariant property does not mean there is only a single possible BST for a given set of data. For instance, consider the person objects, bhagavatula, agarwal, and bain. There are 5 possible BSTs containing those 3 persons (i.e. 5 different BSTs that all have the required invariant). For this question, find all five (distinct) binary search trees that contains the three person objects bhagavatula, agarwal, and bain and save all five of them in a list called the-bsts. That is, your code should look like:

(define the-bsts

(list TREE1

TREE2

...

TREE5))

Hint!

Below are two of the five binary search trees (draw the remaining 3 out on paper before telling DrRacket what they look like):

| One Possible BST | Another Possible BST |

|---|---|

|  |

Counting binary search trees!

If you are a math enthusiast...can you construct a recurrence that calculates the number of binary search trees of nodes? This sequence of numbers is famous enough to have its own name: Catalan numbers.Activity 5. list-all-ssns

Now that we’ve practiced defining some BSTs, write a function called list-all-ssns that takes a binary search tree as input and produces a list of all the SSNs in the tree, in ascending order.

- If the tree is

false, it should return the empty list. - Otherwise, the tree must be a node, so it should generate a list starting with all the SSNs in the smaller subtree, followed by the SSN of the person of that node, followed by the SSNs of the larger subtree.

You MUST use/exploit the invariant in your definition of list-all-ssns. You MAY NOT use a sort function to sort your list.

; list-all-ssns : binary-search-tree -> (listof number)

; takes a search tree and returns a list of all of the SSNs

; of all the people in it, in ascending order

; You MUST exploit the invariant in your solution

; You may NOT use any kind of sorting function.

(define (list-all-ssns tree)

...)

Hint 1

You can use eitherHint 3

Remember, a BST's structure means if we go down one branch we get one kind of SSN...if we go the other way, we get a different one!Hint 4

The way this BST is structured, if you want to visit nodes in order you need to check the left child first, then check the parent node, then check the right child..._but you must do this recursively_.Activity 6. lookup

Define a function lookup that takes a SSN and a binary search tree as inputs, and returns a string – either the name of the person with that social security number or the string not found if the person is not in the tree of the given node.

In other words,

- If the tree is

false, you should returnnot found - Otherwise, the tree must be a node. Check to see if the node’s person is the one you’re looking for. If not, then try the smaller or larger subtree, as appropriate.

You MUST use/exploit the invariant in your definition of lookup. You MAY NOT use a sort function or search areas of the tree you do not need too.

; lookup : number binary-search-tree -> string

; returns name of the person in the tree with that SSN, if there is one

; or "not found" if there isn’t.

(define (lookup social-num tree)

...)

Appendix: Creating Test Cases

In general, creating a comprehensive set of tests is a difficult task. However, just in the context of exercises 4 and 5, a useful strategy is to follow the data definition.

; An ancestry-tree is either...

; - empty

; - (make-human string ancestry-tree ancestry-tree)

To come up with an ancestry-tree, it suffices to pick one of the cases and repeatedly replace any remaining ancestry-trees using the same procedure. Here are a few examples:

Example 1

ancestry-tree ---pick the empty case---> empty

Example 2

ancestry-tree

---pick the make-human case--->

(make-human "A" ancestry-tree ancestry-tree) ; ---pick the empty case--->

(make-human "A" empty ancestry-tree)

; ---pick the empty case--->

(make-human "A" empty empty)

Example 3

ancestry-tree

---pick the make-human case--->

(make-human "B" ancestry-tree ancestry-tree) ---pick the make-human case--->

(make-human "B"

(make-human "C" ancestry-tree ancestry-tree)

ancestry-tree)

; ---pick the empty case twice--->

(make-human "B"

(make-human "C" empty empty)

ancestry-tree)

; ---pick the empty case--->

(make-human "B"

(make-human "C" empty empty)

empty)

In each step, there are exactly two options available from the data definition. Following both options is effectively the same as enumerating all small ancestry trees. Although deciding the names in the trees still requires creativity, at least this approach lets you test the recursive structure in the code.

Double Checking your Work

Make sure you’ve followed the process outlined in the introduction for every function, and that you’ve thoroughly tested your functions for all possible edge cases (i.e. outliers that might affect your function’s definition). Before turning your assignment in, run the file one last time to make sure that it runs properly and doesn’t generate any exceptions, and all the tests pass. Make sure you’ve also spent some time writing your OWN check-expect calls to test your code.