NOTE: Reminder that this assignment is not covered by the Emergency Grade Erasure policy.

Submitting

Regardless of how you choose to complete the assignment, you MUST submit the file you worked on to Canvas.

If you’re submitting remotely, your submitted file will be graded for completeness and correctness via an autograder. Make sure your functions are named correctly and that all of the built-in check-expects pass.

If you’re submitting in-class, make sure to check-in (there will be one question called CHECK-IN Q only available for the first 7 minutes of class) and check-out (there will be a three question survey called CHECKOUT SURVEY only available for the last 10 minutes of class) using PollEverywhere with your location verified.

Structure of a Game

This assignment will start here in the tutorial and then be finished in Exercise 9.

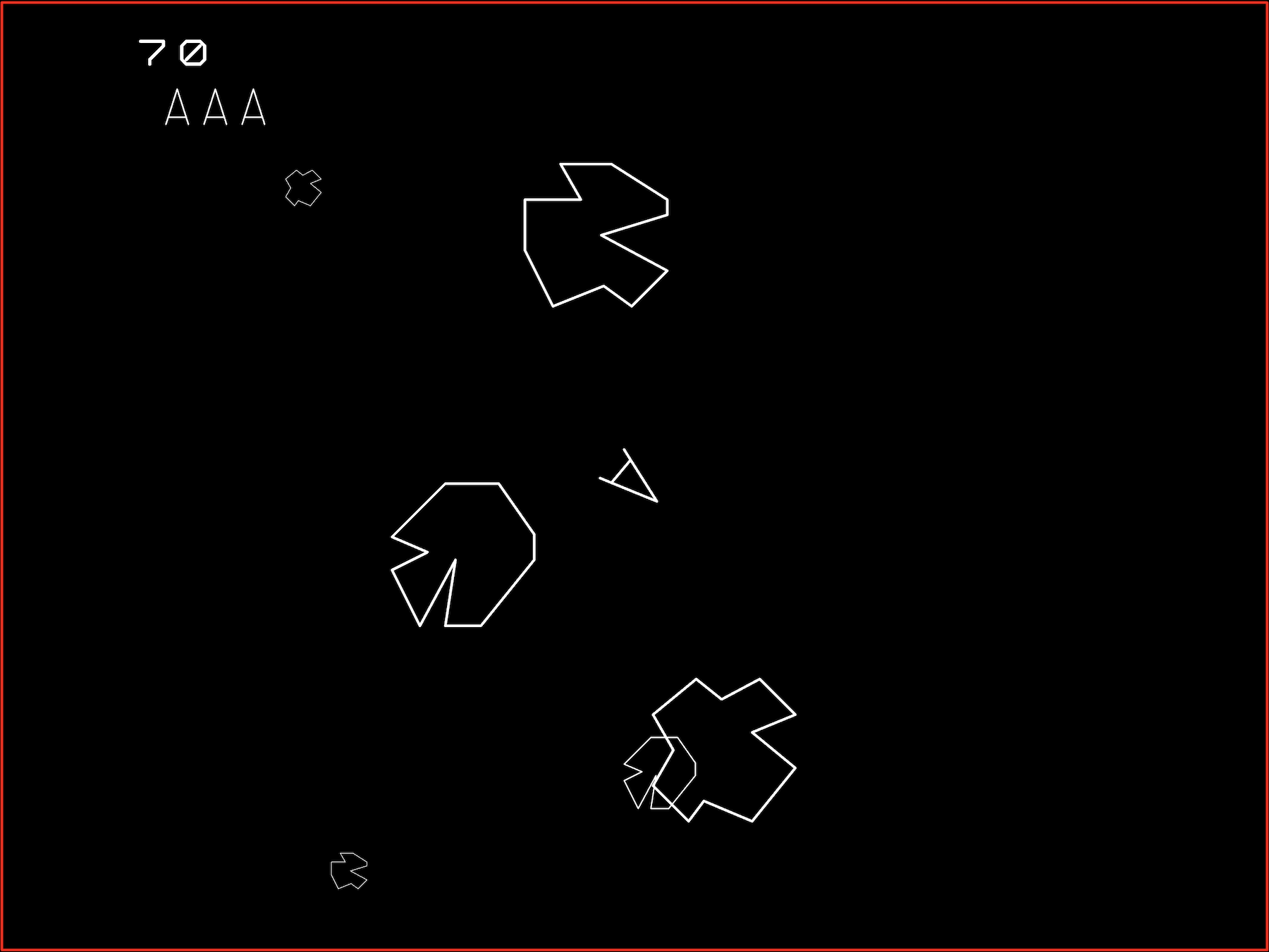

In this tutorial we’ll do a simple re-implementation of the classic arcade game Asteroids. Since this is your first imperative programming activity, we’ve already implemented most of the core functionality for animation. Today we’ll be working on the rendering aspect of the game and then you’ll be focusing on the mechanics and extensions of the game in the Exercise.

Most computer games consist of a set of objects that appear on screen. For each object on screen, there is a data object in memory that represents it, along with functions for redrawing it on the screen and for updating its position and status. The overarching structure of the game really just a loop that runs indefinitely: first calling the update function for every object and then calling the render function for every object. Once the rendering part is complete, the whole process repeats. We’ve already implemented the main game loop and drawing functionally for you so today you’ll be focusing on the code for the update functions.

This will be similar in approach to our work on Snake. Except, now we have imperatives so we have the ability to update structs rather than having to make whole new ones and methods that will simplify our game design.

Intro: Asteroids

Asteroids was an incredibly popular multi-directional arcade game written by Lyle Rains and Ed Long and released by Atari in 1979. It’s now considered one of the most influential video games of all time, both for its effect on players as well as game developers. The objective of the game is to shoot asteroids moving about in the game space while avoiding collisions with your ship and sometimes fending off attacks from enemy spaceships. If you’ve never played the game, there’s a fully functional version available here on the web.

The game was developed for an 8-bit microprocessor (the MOS Technology 6502) which ran at a clock speed of between 1 and 2 MHz. What this technically means is outside the scope of this class…but for a very rough comparison of computing power, odds are your current laptop is running at a clock speed of around 3GHz (or 3000MHz) (and probably has upwards of 4 cores running at this speed). That means your computer is roughly twelve-thousand times more powerful than the original computer than ran Asteroids. Really this is mostly just a fun fact and doesn’t affect this assignment, but I like looking back at computer history to see how far we’ve come.

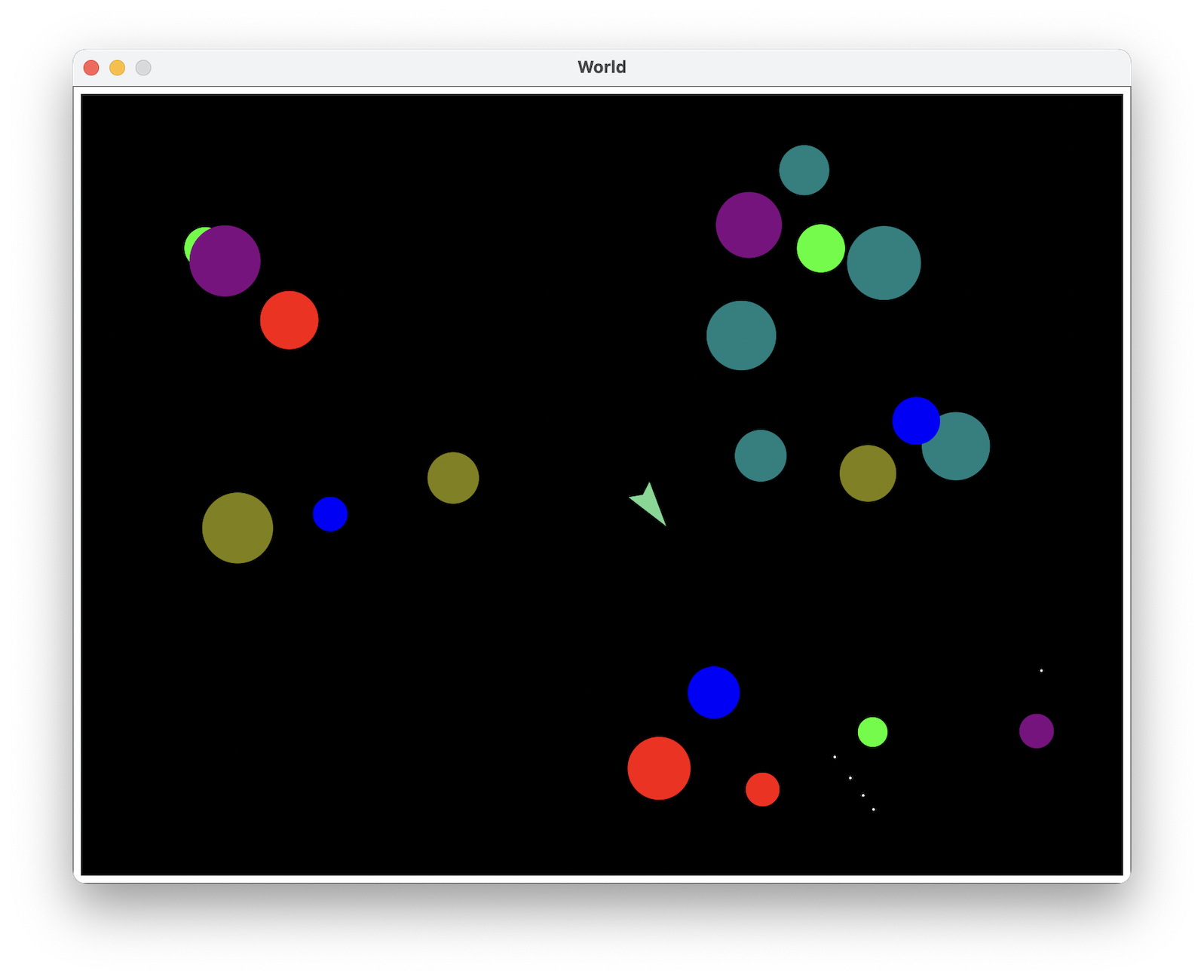

Today, you’ll be finishing up an implementation of a simplified version of asteroids that isn’t feature complete (i.e. it doesn’t have all of the features of the original game) but does emulate its core functionality.

Our simplified game (in the tutorial) will consist of three kinds of on-screen objects:

- some

asteroids which are randomly sized obstacles that float around the screen - a

player, which tries to navigate the space without crashing into one of the asteroids -

missiles, which the player can shoot from the ship to blow up the asteroids in its path

And in the Exercise you’ll add:

-

ufos, which are enemies that try to get the player -

homing-missiless, which are special missiles that track objects

In our game, the-player will pilot the ship using the arrow keys on the keyboard. The left and right keys turn the player’s ship while the up arrow accelerates it in the direction it’s pointing. The space bar fires a missile. The s key fires a homing-missile (you’ll add this in the Exercise). The players’s goal is just to survive as long as possible and not get hit by an asteroid.

Getting Started

Start by opening the tutorial_10.rkt file. You can start the game by calling the asteroids function (no inputs) in the REPL. You can stop it by closing the game’s window. At the moment, much of the player’s control doesn’t work and the visuals leave something to be desired.

Reminder!

If you decide to become any sort of programmer or software engineer later in life, this sort of task will become very familiar. You're given a large existing code base and asked to add new functionality. Before you can add the new functionality, you need to spend some time familiarizing yourself with the existing code. This is why it's so important to write readable and well-commented code because at some point...the roles will be reversed! Make sure to watch the pre-recorded lecture videos as they'll give you insight into how the game engine for Asteroids actually works.Part 0A. Understanding Asteroids Lib

If you’re unsure of what to do at any given point, just come back to this section. This section contains a description of most of the code in the tutorial_10.rkt and asteroids_lib.rkt file that you will need to complete the assignment.

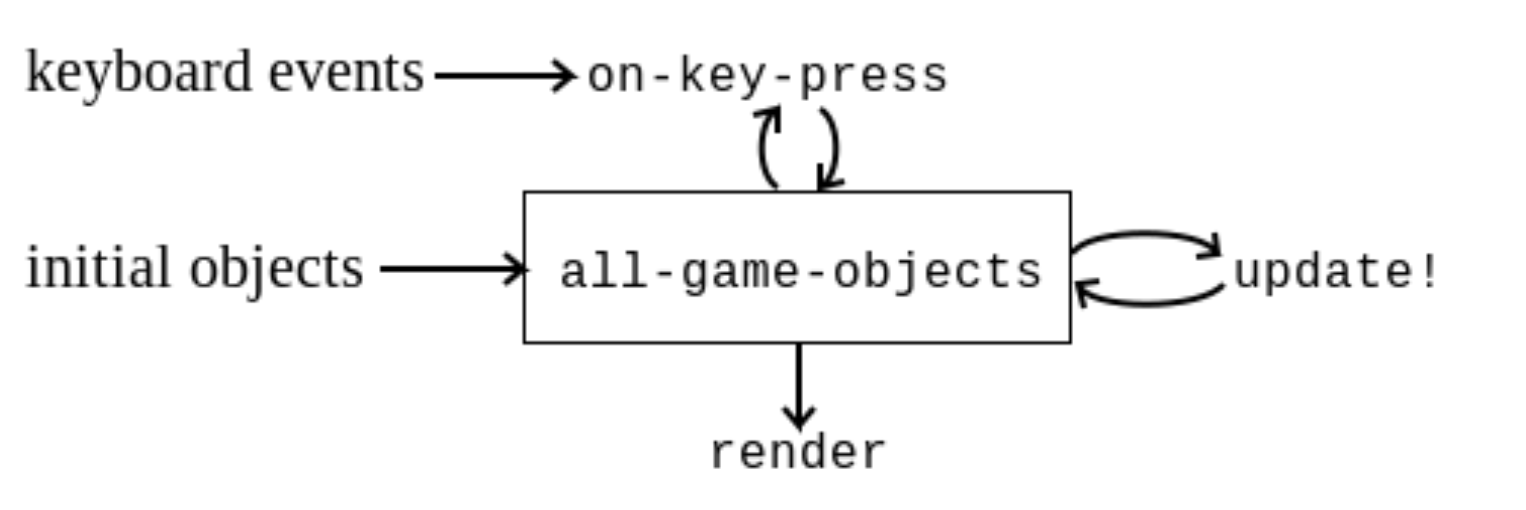

The code of Asteroids is structured around the primary game state, the collection of all game-objects, and an event loop that continuously accepts keyboard events and updates the game state (this mostly happens in the asteroids_lib.rkt library).

When the game is running, the event loop calls an update! method on each object in the game state to update their positions and velocities; then uses the render method to repaint the screen at a rate of 30FPS (frames per second). The event loop also dispatches the keyboard events to the on-key-press function. The on-key-press function then adjusts the player’s orientation and/or creates new missile objects accordingly

You’ll be working on defining what the game objects are (properties/fields) and what they do (methods) in the tutorial_10.rkt file. After you add a feature, make sure to both write some check-expects but also actually run the game by calling the asteroids function in the REPL.

The game-object Struct

Each of the on-screen objects is represented by a data object with a set of built-in properties used by the animation system. We will use game-object as an abstract type, in other words, it’s just a template for other structs and we won’t be creating any game-objects directly.

The starter code provides three kinds of structs: the player, the asteroid and the missile. All three kinds of structs inherit the game-object struct:

;; A game-object is a (make-game-object posn posn number number)

(define-struct game-object

(position velocity orientation rotational-velocity)

#:methods

...)

Every instance of game-objects comes with (at least) four pieces of data that is available through the usual accessor functions:

- The

positionfield: stores aposnstruct representing the position of the object on the screen. - The

velocityfield: stores aposnstruct representing the velocity of the object. The velocity is a vector. - The

orientationfield: stores anumberrepresenting the angle between the object and the x-axis in radians. Note that in the computer’s coordinate system, the y-axis points downwards unlike in Snake. - The

rotational-velocityfield: stores thenumberrepresenting the angular velocity (think of it like spin) of the object (rad/s).

Reminder!

Since we are working with imperative language features, all four fields come with mutators, e.g.Additionally, a game-object has four methods defining its behaviors:

-

; update! : game-object -> void: theupdate!method defines the behavior of each kind of game object. Each different sub-struct should implement its ownupdate!method to update their state. The event loop calls theupdate!method on each game object 30 times per second. -

; render : game-object -> image: therendermethod defines the appearance of each kind of game object. It should return animage. The event loop calls therendermethod on each game object and draws the resulting images on the screen. -

; radius : game-object -> number: theradiusmethod returns the size of each game object. The size must be a positive number. This method is used for collision detection. -

; destroy! : game-object -> void: thedestroy!method implements destruction of a game object. The event loop calls thedestroy!method of a game object when it collides with another game object. The default implementation ofdestroy!in game-object simply removes itself from the globalall-game-objectsvariable that holds the list of all game objects.

The Game State

The game state consists of three variables:

- The variable

all-game-objectsis alistholding all of the objects in the game. Each object is an instance of thegame-objectstruct (or its sub-structs). - The variable

the-playercontains the player struct instance of the game. - The variable

firing-engines?is abooleanflag indicating whether the engine is currently on (#true) or off (#false), and hence indicates whetherthe-playershould be accelerating or not. When the user presses the “up” key, the Asteroids library setsfiring-engines?to#true(you do not need to do this; it will do it for you). When the user releases the “up” key, the Asteroids library setsfiring-engines?to#false(again it will do it for you).

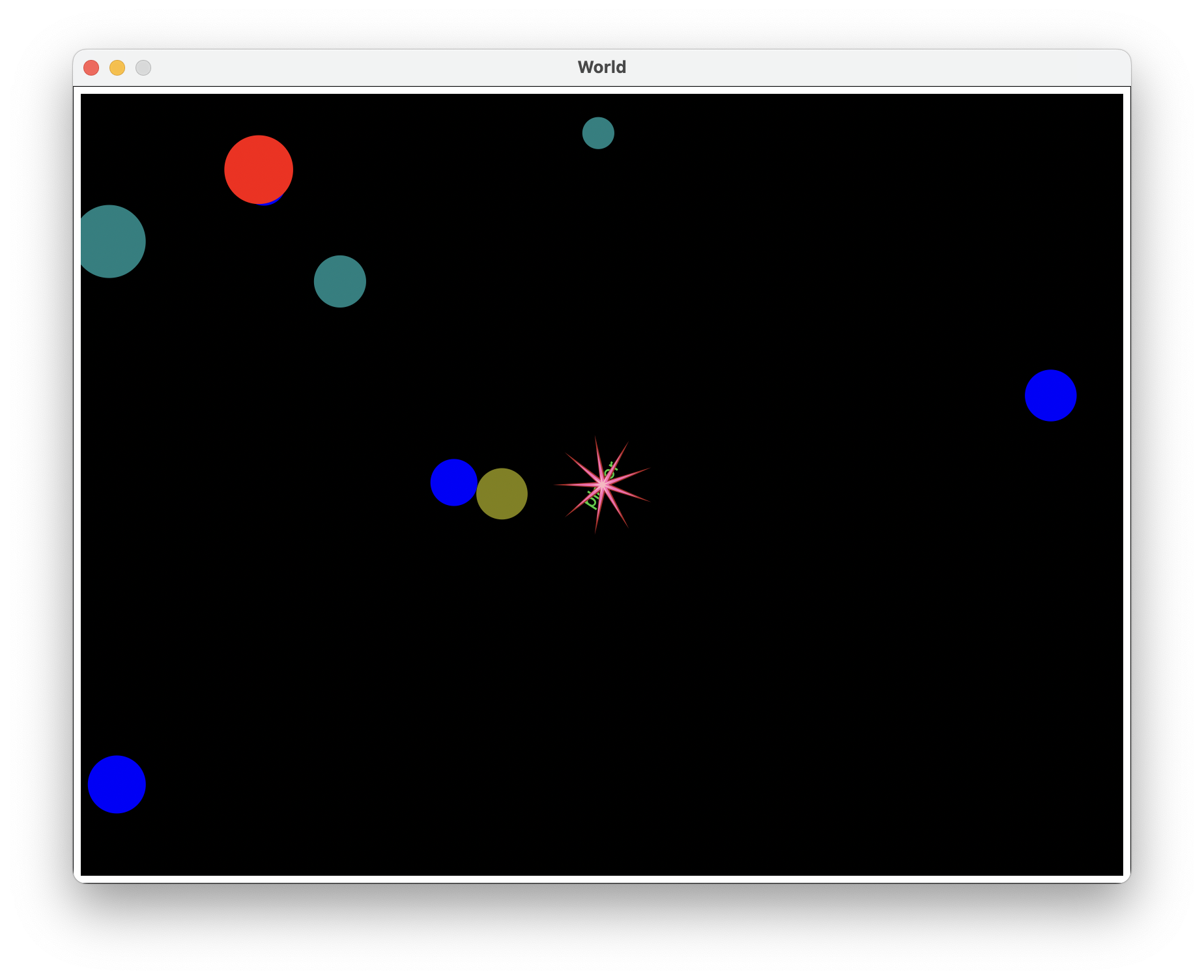

Note that your player won’t respawn when it dies. It’ll just “explode” like in the below screenshot. To play again, just close the window and rerun (asteroids).

Part 0B. Programming movement in Asteroids

The game code uses the posn (short for position) struct to represent positions in space along with velocities of travel. The posn struct is built in but behaves as if you had defined it as we normally do with custom structs:

; a posn is a (make-posn number number)

(define-struct posn (x y))

In other words, you DON’T need the above code and instead the posn object already contains two fields, x and y, accessed with the posn-x and posn-y functions, respectively, which store the x and y coordinates of the point, respectively, and you can create a new posn object by saying (make-posn x y).

- When a

posnis used to represent a point in space, thexandyfields hold the coordinates of the point on the screen, in units of pixels. - When a

posnis used to represent a velocity, thexfield holds the number of pixels per frame that the object is moving horizontally, and theyfield holds the number of pixels per frame that it’s moving vertically.

Adding a velocity to a point

If you want to shift a position by a specified velocity, you can use the posn-+ function.

; posn-+: posn posn -> posn

(posn-+ a b)

This returns a new posn whose x coordinate is the sum of the x coordinates of the inputs and whose y coordinate is the sum of the y coordinates of the inputs. So if you have a location on the screen, represented by a posn, and an amount you want to shift it by, also represented by a posn, you can find the shifted position by adding them with posn-+. For example, if we shift the position (make-posn 1 2) right 3 units and up 4 units, we get the position (make-posn 4 6):

(check-expect (posn-+ (make-posn 1 2)

(make-posn 3 4))

(make-posn 4 6))

Scaling a velocity by multiplying it

You can scale a velocity, represented by a posn, to be “faster” or “slower” by multiplying it by a number. If you multiply it by 2, it moves twice as fast in the same direction. If you multiply it by a half, it moves half as fast, again, in the same direction.

; posn-*: number posn -> posn

(posn-* num posn)

Multiplies num by posn. The x and y coordinates of the original posn are each multiplied by num. For example:

(check-expect (posn-* 2

(make-posn 3 4))

(make-posn 6 8))

Sensing the Player’s Input

You won’t need to worry about this as asteroids_lib.rkt takes care of all of this but it works the exact same way as Snake. When the user hits a key, the game “hears” the key and calls the appropriate function.

Part 1. The player Struct

We’ll start by completing this part in the tutorial today. The further you get in this assignment today, the less work you have to do in Exercise 9. If you do not finish today, you’re still responsible for the stuff in this assignment as Exercise 9 will assume you’ve already finished this part.

Let’s start by implementing the player struct. Right now, the player does not respond to the user’s command because it inherits the default update! method from game-object which does nothing. Complete the update!, render and radius methods for the player:

- The

rendermethod returns theimageof the player. - The

radiusmethod returns the size (number) of the player. The size must be a positive number and needs to represent a “bounding circle” around your chosenimagefor the player. See the pre-recorded lecture for more details. - The

update!method should speed up the player in forward direction (i.e. appropriately mutates the velocity field) when the engine is on.

Hint on render

You may pick any design you like as the appearance of the player object in the render method and any size appropriate in the radius method. The size usually matches the image of the player object. For more information about how the Asteroids library uses the

If you are using an image with a "clear forward direction" (like a triangle) draw it so that the "forward point" is pointing directly to the right as the game engine will initialize your player as if it's facing directly to the right.

Hint on radius

If you're using a basic image for your player, then this function will likely be super simple. Say you have a triangle with a base width of 10. That means a bounding circle around that triangle would need to have radius 5. So your function would literally be

More details on update!

We'll need a little basic physics knowledge to get this working. Acceleration is just a fancy word for "increasing velocity." That means, in order to accelerate the player, we need to increase (mutate) its velocity.

Step 1. We need to review Part 0A to find some property of the game state that indicates whether or not the engine is currently firing.

Step 2. We need to figure out how to mutate the velocity of the player (Part 0A).

Step 3. We need to write an expression to tell the player to accelerate (Part 0B).

In other words, let

(set-game-object-velocity! p (posn-+ (game-object-velocity p)

acceleration-expr))

- The velocity

v is computed by the function call(game-object-velocity p) . - The vector addition,

v+a , is calculated using theposn-+ function. -

acceleration-expr is an expression computing the acceleration,a , pointing in the forward direction.

; forward-direction: game-object -> posn

; Returns a unit vector in the forward direction of the game object.

Finally, remember you only need to change the acceleration when the up key is being held down. You do not need to decelerate the player. You can "slow down" in the game by turning around and accelerating in the opposite direction.

Part 2. The asteroid Struct

In the next step, let’s enrich the game with asteroids of different sizes and different colors. To achieve this goal, we define the asteroid struct with two additional fields storing the radius and the color information:

(define-struct (asteroid game-object) (radius color)

#:methods

...)

- The

radiusfield stores a positive number representing the size of an asteroid. - The

colorfield stores the color of an asteroid. It is a string or an RGB color struct.

Your task is to implement the radius method and the render method for asteroids. The Asteroids library takes on the job of creating asteroids with varying radii and colors and will also take care of updating the asteroids state (i.e. you don’t need an update! method for asteroids).

- The

rendermethod returns an image of the asteroid. - The

radiusmethod should return the size stored in the radius attribute (i.e. it won’t return a fixed number)

Note: The asteroid struct purposefully has both a radius attribute and a radius method. There isn’t a name conflict here, because in order to access the property radius of an asteroid we use the accessor asteroid-radius which is distinct from the radius method which we’d call by saying: (radius an-asteroid).

Part 3. how-many-of Function

In the next part (and in the exercise), you’ll be asked to limit the number of missiles (and later homing-missiles) on the screen at any given time. In order to do that, we need some way of counting how many of some object there are already in the game. To do that, write a function with the following signature and purpose:

; how-many-of : (game-object -> boolean) -> number

; calculates how many of some game-object are currently in the game

Notice this is a higher-order function. The inputs to this function will always be on the of the automatically defined predicates from define-struct. Remember, you can access the list of all game-objects through the all-game-objects list.

Part 4. The missile Struct

Finally, finish the base game by implementing the missile object and limiting a missile’s lifetime on the screen. A missile self-destructs when it reaches the end of its lifetime.

(define-struct (missile game-object) (lifetime)

#:methods

...)

- The

lifetimeattribute stores an integer between 0 and 100 representing the current remaining life of a missile. - The

update!method should decrement the lifetime of a missile by 1 if its remaining lifetime is positive before the decrement.- Unless there are fewer than 10 missiles in the game, call the

destroy!method on this missile. (Recall that you just wrote a functionhow-many-of…) - When the lifetime of a missile is already 0 (so decrementing it would have ended up with a negative number), call

destroy!to destroy the missile. Theupdate!method does NOT need to move the missile.

- Unless there are fewer than 10 missiles in the game, call the

- The

rendermethod returns an image of the missile. - The

radiusmethod returns the size of the missile. It should be a positive number and may be fixed since you are designing the image of the missile.

Note that the game engine will take care of actually moving the missile across the screen (which it will NOT do for the homing-missiles in Exercise 10).

Testing your Work Before Submitting

There are some built-in tests that we’ve provided, but also consider other ways you might test your completed work.

Make sure to actually try playing the game! Does it work as expected? If everything was defined correctly than you should have a working simple asteroids complete with moving asteroids, a possibly-moving/rotating/missile-firing/possibly-losing player, and destroyable asteroids.