Note: For groups that may have a significant amount of programming experience, your PM may suggest trying out the Advanced Tutorial 4

Submitting

Regardless of how you choose to complete the assignment, you MUST submit the file you worked on to Canvas.

If you’re submitting remotely, your submitted file will be graded for completeness and correctness via an autograder. Make sure your functions are named correctly and that all of the built-in check-expects pass.

If you’re submitting in-class, make sure to check-in (there will be one question called CHECK-IN Q only available for the first 7 minutes of class) and check-out (there will be a three questions survey called CHECKOUT SURVEY only available for the last 10 minutes of class) using PollEverywhere with your location verified.

Getting Started

Today’s tutorial is all about practicing recursion. Remember, recursion itself is a very simple concept: a function is recursive if it calls itself in its definition. In all of these, we AREN’T using our list iterators (e.g. filter, map, etc.). Instead, we’re building these functions from the ground up!

Relevant “XKCD” Comic Strip (totally worth a click):

There are no template files for this Tutorial so you’ll need to start from a blank DrRacket file. You can do this by either just opening DrRacket and it’ll open a new Untitled file or if you already have DrRacket open, you can go to the File menu and hit New or New Tab.

After you’ve got a blank document open (make sure you’ve got your language chooser line at the top #lang htdp/isl+), might as well save it with a good sensible name somewhere on your computer where you store important docs.

Part 1. factorial

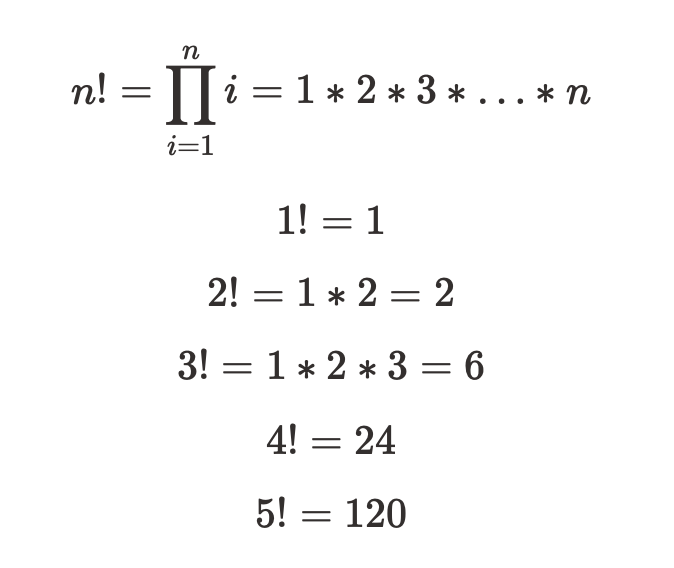

Write the factorial function n! as a recursive function. The factorial of a number is the product of all the numbers from one to that number:

and so on. Here are some subgoals to accomplish on your way to writing the function:

Subgoal 1. What is the type of factorial (that is, what is its type signature, the types of its input and output)?

Subgoal 2. What is the purpose statement for it? Can you write some tests (check-expects) to make sure it works?

Subgoal 3. What should the base case be (aka the “easy case”) for the recursion. The base case is an input for the function where you know the answer without having to recurse. What’s a really easy input to compute the factorial of?

Hint: what’s 1!?

Subgoal 4. Now time to implement that base case. Write inside your function (this is just a temporary “stub”):

(if test-for-base-case

answer-for-base-case

TODO)

Now replace test-for-base-case with something that looks at the input to the function and determines if it’s the base-case input, and answer-for-base-case is the answer for the base case. We’ll fill in TODO in a minute.

Hint (again): Let’s say you named your input to the function

n. If we know that(factorial 1)should be1cause1!is 1…and we know that1!is our “simplest” (base) case…then all we need to do is test to see ifnis=to1. If it is…then our function should just return1.

Subgoal 5. What’s the recursive case? The recursive case is what runs when the input is anything that’s NOT the base case. Basically, our goal is to call ourselves (i.e. factorial) with a new input that’s “one step closer” to the base case. Once we get that answer back (it could take a lot of recursions), we’ll take the answer to that and turn it into the answer for the original problem.

You’ll need to decide two things:

- How do you make the input to

factorialbe “one step closer” to your base case? - If you had the answer for the “one step closer” input, how would you use it to solve for the original input?

Hint: how would you make

3!one step closer to1!? Wait a second…isn’t3!the same thing as3 * 2!? And isn’t2!the same thing as2 * 1!?

Subgoal 6. Now fill in the part in your code that says TODO:

- Write your recursive call, i.e.

(factorial easier-input)whereeasier-inputis whatever the easier version of the input is -

easier-inputwill look some thing like this(some-math-op input-number another-number) - Then change it to

(fixit (factorial easier-input))wherefixitis something that transforms the answer to(factorial easier-input)into the answer for the original input.

Note: our notation here is a little misleading because it makes it look like

fixitshould just be the name of a function. But for this problem, you’ll want to pass an additional argument to the function besides the result from the recursive call. That means for this problem, the form will really be:(some-function some-argument (factorial easier-input))

Hint: Remember, that a factorial can be expressed like this:

5! = (5 - 0) * 4! = (5 - 0) * (5 - 1) * 3! = ...

Nice work! You’ve officially written a recursive function. Remember that all you need to do is: 1. find a base case; 2. think of a way of getting the original input “one step closer” to the base case at a time; and 3. think of a way to combine the results to the “one step closer” problems into the larger problem.

Having trouble? See if this walkthrough step-by-step helps.

Part 2. count-odd

Write a function

count-odd: (listof number) -> number

that returns the number of odd elements in a list of numbers. Remember that you can determine if a number is odd by calling the predicate odd?.

Subgoal 1. We’ve already given you a type for count-odd. So write a type signature comment.

Subgoal 2. Now write a purpose statement in your own words. Don’t start writing code before you start thinking about what you’re trying to accomplish! Can you write some check-expects to verify it works as you might imagine?

Subgoal 3. Okay, now what’s the base case? Again, this is a case that’s so easy we don’t have to do much. What would be a list where you’d just know the answer?

Subgoal 4. Write your skeleton for a simple recursion:

(if base-case

base-case-answer

TODO)

and fill in the first two parts.

Subgoal 5. Now what’s your recursive case? Again, this has two parts:

- What’s an easier input that’s “one step closer” to your base case?

- How do you transform the answer for the easier input into the answer for the original input? Transforming the answer for this one is a little more complicated because it requires its own

ifexpression.

Note: It might be useful to remember two convenient

listfunctions,firstwhich returns the first element of a given list andrestwhich returns all of the elements except the first one. Check it out in the documentation or in our function glossary.

Subgoal 6. Finally, fill in the TODO part with your full recursive case. Normally, the recursive case would look something like:

(fixit (count-odd easier-input))

However, since the fixit part here needs to involve an if expression that will use the answer from the recursive step a few different times, it’s probably easier to put the result of the recursive call into a local variable using the local expression.

Your code will look something like:

(if base-case

base-case-answer

(local [(define recursive-answer (count-odd easier-input))]

(if something-is-true

do-something

do-something-else)))

And then recursive-answer will get used inside of two of the do-somethings.

Wow, you’re good at this! Two down, two to go!

Sussman Form

So, as is the case with many classes…we’ve been lying to you for the last few weeks. You know how I said you HAD to use lambda or the λ to define a function? Totally not true. Say you have a function like this:

(define i-am-so-cool

(lambda (an-input)

do-something-cool))

You can actually use Sussman form as a short hand for this same definition by doing the following:

(define (i-am-so-cool an-input)

do-something-cool)

These two things are completely equivalent. In fact, Racket will run your code in the second example…add the lambda expression back in to your code and then run it as normal. There is never a case where you have to use Sussman form, it is what’s often referred to as “syntactic sugar.” However, you’ll start seeing it in our example files from now on as it’s just a tad faster than having to type lambda.

So in the general case, a function in Sussman form just looks like this:

(define (function-name input-1 input-2 ...)

output-expression)

One last example just to make sure you see the difference in notation. These two function definitions are EXACTLY the same:

(define f

(lambda (x)

(+ x 2)))

(define (f x)

(+ x 2))

Like I said, you don’t have to use Sussman form. But it is quicker to type…so see if you like it in the next couple of problems.

Part 3. count

Now abstract your answer from the previous question to make a function

count: (T -> Boolean) (listof T) -> number

that takes a list, but also a predicate, and returns the number of elements in the list that the predicate returns true. For example, (count odd? my-list) should do the same thing as (count-odd my-list).

Good news! This does not require coming up with a new base case or recursive case. It requires only abstracting your code (remember, abstraction is both powerful and cool). That is, you should:

- Copy your code for Problem 2

- Change the name of the function

- Add an extra input to the function so that the user can input a predicate

- Change the code so that instead of always using

odd?it instead uses the predicate the user specified. (Make sure to change therecursive-answer!) - Make sure to write some tests for your new function!

Wow. Abstraction and recursion. This is straight 🔥. Better call the 🚒.

Part 4. Seeing the trees from the Forest

Write a recursive function, tree, that makes a recursive image something like this:

How do you make something like this? Here’s the basic idea:

- At its base, it’s just a solid green rectangle

- Then, we have just two solid green rectangles rotated at say a 45 degree angle

- REPEAT FOR ALL GREEN RECTANGLES (until you feel like stopping)

Another way of describing it is that tree is a stick for the trunk and then two simpler trees sticking out of it at angles. Those simpler trees are each sticks with two simpler trees sticking out of them at angles. And so on, and so on, until eventually it just draws a stick.

We can write that as a recursion. The function tree takes a number of levels of branching (levels of recursion) and gives you back an image of that tree with that number of levels. So zero levels of branching is just a stick. One level of branching is a Y shape (a stick with two sticks pointing out of it), two levels of branching is a Y where the branches on top each each Y’s themselves, and so on. That means:

- A tree with zero levels of branching is a stick

- A tree with

nlevels of branching is a stick with two subtrees that haven-1levels of branching

Here’s what your function should (roughly) produce across inputs from 0 levels of branching up to 9 levels:

Your trees don’t have to look exactly like ours–that would require a lot of trial and error that you wouldn’t learn anything from. Just experiment with making recursive pictures like this and have fun. You can make some absolutely dope images with this simple pattern.

Note: remember that you’ll need to add

(require 2htdp/image)to your file to get access to the graphics functions.

Time for some subgoals:

- As always, what is the type of the function? That is, what type of input does it expect and what type of output does it generate? Remember that the input is the number of levels of branching (i.e. number of levels of recursion).

- Write a type signature comment.

- What is it trying to do in your own words?

- Write a purpose statement (it’s hard to write tests for this sort of image function, so instead try to imagine what sort of images you SHOULD see as soon as your program starts working)

- What’s your base case? That is, for what number of levels of branching do you not need to recurse at all? And what do you return then?

- What’s your recursive case?

- What’s the “one step closer” number of levels of branching that brings you closer to the base case?

- When you recurse, you’re going to make a subtree and you’re going to paste it into the final output twice. So you might as well do just one recursive call and put it in a local variable using local. So write something that looks like:

(local [(define subtree (tree simpler-input))]

TODO)

Note: that is NOT a function definition in Sussman form. That is storing the result of running

(tree simpler-input)in the local variable subtree

- Finally, you need to fill in

TODOwith something that makes the subtree itself by assembling the two copies of the subtree with a trunk. Rather than make you fiddle for a long time, here’s the basic structure, which is:

(above (beside (rotate angle (scale factor subtree))

(rotate (* -1 angle) (scale factor subtree)))

(rectangle ... some pretty args ...))

Pick whatever angle you want (we used 45 degrees). For factor, choose some number less than 1, so that the subtrees are smaller than the original stick (by a factor of…well…factor). And for rectangle, use whatever arguments you want, but you want to be sure the rectangle is narrow and tall.

Feel free to experiment. You can add little circles at the ends, for example to make something that looks vaguely like leaves. There’s no specific right answer we’re looking for on this one.