Feel free to take a look at this tutorial in advance, but since attendance is required this first week so you can meet your team, you do not need to actually work on it until class on Wednesday.

Submitting

Regardless of how you choose to complete the assignment, you MUST submit the file you worked on to Canvas.

IF YOU ARE SUBMITTING REMOTELY

This is not an option for this first tutorial. Come meet your tutorial team. In future weeks, you can choose to do this and your file will be graded for correctness.

IF YOU ARE IN CLASS OR AT AN ALT TUTORIAL

Then your file will be graded for participation (i.e. it’s okay if you haven’t finished the entire thing because you may have spent time asking a question; helping a friend; etc.) along with what we call a ‘peer review.’ Find one other person in your group that is finished and peer review each other’s work. Here are the things to check:

- Does their code look readable and neat?

- Can you understand what their code does by reading it?

- How was their solution different from yours (if at all)?

- Does their program run and generate the correct results?

To prove you’re in attendance, please see the instructions on the projector.

You’re free to go after you’re finished, though we hope that you might consider sticking around and helping others in your group.

Getting Started

In this assignment you’ll play with simple functions for making images that we’ll use later on in the course. Make sure to work with the other people in your group. If you find yourself needing help, ask your assigned PM or any of the other course staff members.

Note: For groups that may have a significant amount of programming experience, your PM may suggest trying out the Advanced Tutorial 1

DrRacket’s main interface consists of two main panes, which default to being in Vertical Layout (on one top of the other). The top portion is the Definitions Window where you write your programs and execute them using the Run button at the top of the screen. The bottom portion is the Interaction Window where the results of running your program are displayed. You can also use the Interaction Window to run individual expressions in this window by typing them here and pressing the Enter key. Think of it like a playground where you can test small parts (usually one line or expression) of your program instead of the whole thing.

You can also set DrRacket to be in Horizontal Layout where the Program Window and Interaction Windows are placed in a horizontal orientation. To switch orientations, click on the View menu and select View Horizontal Layout (you can switch back the same way). I’ll usually use Horizontal Mode in class, but sometimes I waffle between the two. Do whatever works for you!

Go to the Definitions Window and add the following two commands to the beginning:

#lang htdp/isl+

(require 2htdp/image)

First we tell DrRacket to load in ISL then we tell it to use a pre-existing software package, specifically the graphics library (which is documented here). Now hit the Run button. That will ask Racket to load the graphics library so you can use it both in the Program and Interaction windows. Important: Racket will only load this library if you click Run. If you don’t hit Run, then Racket doesn’t “checkout the book from the library,” so to speak.

Review

In programming, you do most of your work by calling (or colloquially “running”) functions. Just like in a math class, functions in computer science are basically machines that take in some input(s) and produce some output. In slightly different terms, functions are small programs written by someone else (and later by you) that take some arguments (inputs) and produce some output.

In order to use a function, we use a function call. In other words, we have to give the function its expected inputs and it will in turn give us its output. Racket uses a uniform notation for function calls:

(function inputs ...)

The name of the function you want to run comes first, followed by its arguments, separated by spaces, and the whole function call is wrapped up in a set of parentheses. Different functions require different numbers of and kinds of arguments. For example, the rectangle function requires two numbers (the width and height) followed by two strings (the drawing mode – either "solid" or "outline", and the name of the color to use). So we can make a 50x50 blue rectangle by saying:

(rectangle 50 50 "solid" "blue")

Try running that program now in the Interaction Window (sometimes called the REPL which we’ll talk about more later).

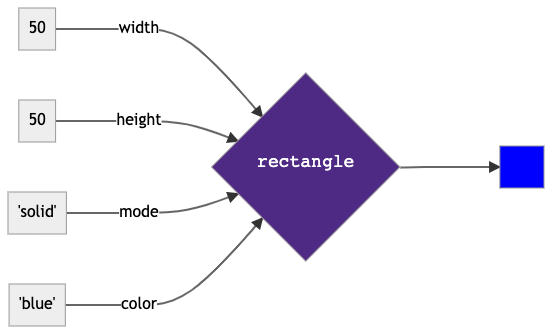

We call the rectangle function, passing it the inputs 50, 50, "solid", and "blue". Its output is another data object: the image of a blue square. Here’s what that whole process looks like in a data flow diagram.

Try changing the arguments to different values and rerunning the expression. Change the width and height, the color, etc.

All the functions in Racket are documented in the official Racket Documentation. There are lots of ways to lookup documentation for functions in ISL+.

- Look up the documentation on the

rectanglefunction. - See how it explains each of the inputs.

- The funny notation, like

(and/c real? (not/c negative?)), is short-hand for “a possibly fractional number that isn’t negative.” - You can click on

mode?to see which other drawing modes are allowed.

- The funny notation, like

- Now look up the documentation for the

ellipsefunction. What’s similar? What’s different?

Note: In this class, it’s generally a bad idea to copy and paste code from any source, including this document. For one, if you’re copy and pasting, you don’t get the sort of kinesthetic experience of programming. Secondly, many times when you copy and paste from documents and web pages, you accidentally copy and paste so-called “special” characters that look like a character you know, but are slightly different for example:

-and–look VERY similar…but are totally different characters. If you just copy and paste, you might end up with a mix of – and - which will cause lots of confusion down the road. So for all of the function calls we show below…please type them yourself! And thirdly, copy-and-pasting from sources not provided by the class may be a violation of our academic honesty policy.

Part 1. Simple Shapes

Let’s make a series of simple images. Use the relevant Racket functions to create the image you see (the lecture slides might be a useful resource here; as would the official Racket documentation):

First, let’s make a 100 x 100 solid green square.

Next, a blue circle with a diameter of 100.

Part 2. Compound Shapes

Now let’s make compound images from simpler images. For example, what if you wanted to make a shape like the below:

We can do this by first making two shapes and then joining them using a function called overlay. The overlay function takes images as arguments and outputs a new image that contains its inputted images stacked on one another (make sure to look it up in the reference materials!). Notice that this means we’re composing or chaining the calls to our shape functions with the call to overlay.

The outputs of the two shape functions are passed as inputs to overlay. The data flow we want looks like the below: two shape function calls that output each shape, followed by an overlay call that outputs the final image. This one is if you wanted to overlay two concentric (i.e. they share the same center point) circles.

How do we chain calls in our code? By moving the function call into the place where we want it to be used as an input. The three calls we want, written as text, would look like this:

-

(overlay circle1 circle2), wherecircle1andcircle2are the two circles we want to join…(circle 50 "solid" "red")(circle 100 "solid" "blue")

That means we just paste the second two function calls into the first one, replacing our place holders circle1 and circle2:

(overlay (circle 50 "solid" "red") (circle 100 "solid" "blue"))

The problem is this is hard to read because you have to keep track of the parentheses to know what things are inputs to what. To make this more easily to see, we break the function call up into two lines and indent the second line so that the two inputs to overlay line up:

(overlay (circle 50 "solid" "red")

(circle 100 "solid" "blue"))

Once you understand this indentation convention, you can see visually that this is two circle calls feeding their outputs to overlay, without having to figure out the parentheses. Some programmers break it up further:

(overlay (circle 50

"solid"

"red")

(circle 100

"solid"

"blue"))

But this isn’t strictly necessary. The rules you want to follow are:

- Put the first argument on the same line as the function

- Put subsequent arguments on different lines if those arguments are calls themselves

Realize though that this is to make your code more human-readable, and will have no effect on how it gets run by Racket. That doesn’t make it any less important (in fact, I’d argue it makes it MORE important if you ever want to share your code).

Alright, now that you’ve seen an example of using overlay, see if you can adapt it to make a compound image of our blue circle from earlier on top of our green square from earlier like the below:

Of course overlay is just one function that makes compound images. Make sure to check out the other functions that do similar things like above(documentation link) and beside(documentation link).

Part 3. Concentric Diamonds

Reproduce the shape below (don’t worry about exactly matching sizes or colors):

Before jumping in, try to break the problem down into smaller sub problems:

- Find a function in the

2htdp/imagelibrary that produces diamond shapes. - Create a really small diamond.

- Figure out how to make 3 slightly larger diamonds of different colors.

- Finally, take all four of the diamonds and feed them as inputs to a function that allows you to combine images.

This approach is often called sub-goaling and is a particularly important programming practice. Don’t try and approach a complex problem all at once. Instead, identify smaller parts you already know how to do and work towards combining them into the ultimate goal.

Part 4. Writing a Simple Function

Now write a simple function, glasses, that makes a picture of a pair of glasses. It takes two inputs, the first is the lens design (an image) and the second is the design for the bridge that joins the two lenses (also an image). It should output an image with two copies of the lens, joined by the bridge. So if you say:

(glasses (circle 50 "outline" "black")

(rectangle 20 2 "outline" "black"))

You should get something like this:

Remember, a lambda expression is one that allows you to specify something is a function that needs to be evaluated with inputs rather than just a regular old piece of data. So for example, we can make a new function by saying:

(lambda (lens bridge)

output-code)

Where output-code is whatever code you want to use to make the image of the glasses. The word lambda tells the system we’re making a new function, and the (lens bridge) part tells the system that the output code can refer to the inputs passed to the function by the names lens and bridge, respectively. When the function is called, the system will substitute the first argument passed to the function, whatever it may be, for the name lens wherever it appears in the output-code and it will substitute the second argument in for the name bridge.

That’s how you make a new function, but making the function doesn’t give it a name. You do that by wrapping it in a define expression. So, your program should look something like this:

(define glasses

(lambda (lens bridge)

output-code))

Your job here is to decide what output-code should be. It’s going to want to make two copies of the lens and place them around a copy of the bridge. Remember that you can insert whatever the user provided for the lensand bridge into your code just by saying lens and bridge respectively.

Feel free to change the names lens and bridge to something else if you prefer.

Hint: You won’t be able to use

overlayhere since you need to place shapes beside each other. See if there’s another function in the2htdp/imagelibrary that might be useful for combining images in a different way!

Part 5. Designer Eyeware

Now have fun trying to make different interesting glasses designs, and share them with the other students in your group! The wackier the better!